Folks:

Below is the vlog about my Inquiry Project Paper, titled “Web of Conspiracy: Conspiracy Theories as Abusive Political Discourse.” Hope you enjoy.

As always, your feedback is welcomed.

Thanks, Adam

Folks:

Below is the vlog about my Inquiry Project Paper, titled “Web of Conspiracy: Conspiracy Theories as Abusive Political Discourse.” Hope you enjoy.

As always, your feedback is welcomed.

Thanks, Adam

Most of my learning about communications ethics literacy to date has happened at the intersection between theories and real life experiences, primarily at work and in the community. I suppose that is as it should be. But the readings this week provided another unexpected nugget of inspiration: music.

“One cannot force oneself to be a good musician, but if one continues to play and learn content, every now and then emerges a moment between the player and content that takes the music to a place not known before. One cannot demand such revelation, but without the hard work and practice on the content, no revelation will happen.”

(Arnett et al., 2009, pp. 224-225)

In the distant past, I was a serious flute player. Studied privately with a renowned teacher for the better part of a decade, gave concerts, played in various ensembles including the Charlotte Youth Symphony, all-state band and orchestra, and a group called the Charlotte Flute Choir. Once I got to perform for Jean-Pierre Rampal, one of the greatest professional players of all time, in a master class in my family’s living room.

This is all ancient history, as I haven’t picked up my flute in any significant way since shipping out for college. But the visceral memories of playing are still there, and fortunately they include a few revelatory ones to which the statement above alludes. Certainly playing for Rampal was one of them.

The relevance for communications ethics literacy relates to intentionality of effort. Just as with music, meaning will only come from a concerted (pun intended) effort to apply and share what I have learned. In other words, I have to work at it.

There are some basic lenses that I can peer through to actualize learnings in contexts beyond my studies, such as work, community, family and personal life. For example:

These and other guideline are designed to facilitate the communicative good of dialogue, which is vital to discernment. “Dialogue requires that one know the ground from which one speaks, meet the other with a willingness to learn, and learn about the ground from which the Other’s discourse emerges (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 223).” The imperative of a dialogic ethic in all manner of interactions can’t be understated, especially where conflict or disagreement exists.

BAD news: Given the timing of this post, Donald Trump is top-of-mind.

GOOD news: He’s perfect fodder for proving my point.

To me, Trump is the antithesis of communications ethics literacy. His most recent statements about prohibiting all Muslims from entering the United States represent an diametrically opposing praxis (been dying to use that term!) for achieving a dialogic ethic.

Following are Trump’s variations on the guidelines above:

In my professional, community and personal endeavors, seeking dialogue is standard operating procedure for resolving conflict, building consensus, or otherwise working toward mutually beneficial outcomes. More often than not, this is a worthwhile exercise. But it rarely produces something extraordinary or transcendent, an interaction that represents the highest form of communications ethics literacy. Fortunately I’ve had a few revelatory experiences in my life as a musician and otherwise — the ones that marked me indelibly and helped shape me as a communicator, leader and person. With the academic grounding from my studies, I hope there will be more.

Reference:

Arnett, R.C., Harden Fritz, J.M. and Bell, L.M (2009). Communication ethics literacy: dialogue and difference. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

In the many condolence messages that my siblings and I received after my dad died, “a life well lived” was a description often used by his friends and colleagues. Recalling the care for dad as his health failed, it occurred to me that this theme applied not just to the nature of dad’s life’s experience, but the health care communication ethic that characterized the end of that life well lived.

In the many condolence messages that my siblings and I received after my dad died, “a life well lived” was a description often used by his friends and colleagues. Recalling the care for dad as his health failed, it occurred to me that this theme applied not just to the nature of dad’s life’s experience, but the health care communication ethic that characterized the end of that life well lived.

Dad died in April of this year from complications from lymphoma. My mom had died 15 months before, and the communicative actions involved in that experience set an important precedent for how we addressed dad’s illness. The situation was complex, reflecting the distinctive personalities and styles of two elderly parents, six opinionated children, and assorted in-laws and grandchildren. My strong-willed mother refused to accept her increasing physical and mental limitations, and my dad was hesitant to intercede out of fear of causing additional emotional and physical damage to her already frail condition. Both understood yet neither would consciously accept the“final reality” that she was dying. As a result, mom lost the ability to choose the manner in which she would “meet the inevitable” and achieve the communicative good in her care situation (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 195).

My parents’ behaviors were communicative actions that made it difficult for them to achieve quality of life, and for us to render effective care for her leading up to her death. Although my siblings and I were largely unified in our approach, a collective lack of experience and understanding hindered our effectiveness as well. The day that mom died was especially hard, as she was unwilling or unable to clearly tell us what she wanted to happen, leaving us frustrated and upset.

Although the end of mom’s life was largely unsettling, we learned a great deal from the experience that was beneficial when my dad began to decline months later. By and large, my siblings and I followed principles of health care communication ethics. Foremost, we were all committed to his care, comfort and quality of life, exhibiting the essential human trait in our desire to undertake “the labor of care (as) a necessity of our identity” (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 200). We were remarkably unified, with few disagreements about decisions and mutual support for each other emotionally. We each took responsibility for different aspects of supporting and caring for dad, from preparing his meals to accompanying him to medical appointments to having dinner with him most every night. Regular conference calls, emails and texts helped us coordinate and strategize support on his behalf, reflecting the “how” to answer the “why” of providing his optimal quality of life (p. 201).

Dad jokingly nicknamed his six children “the committee” to signify the degree to which we had rallied around him and taken responsibility for his care. Daily interaction between him and us and among committe members reflected a dialogic ethic comprised of “listening, attentiveness, and negotiation” (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 205). This constant giving and receiving of care represented the good inherent in the “pragmatic

necessity of response, readying ourselves for the final freedom – our response to the inevitability of death” (p. 197).

In stark contrast to what happened with mom, I don’t think there was anything we could or would have done differently for dad at the end of his life. He felt nurtured and prepared for what he faced. His death left us profoundly sad of course, but there also was peace and the ability to see and celebrate a life well lived. Ethical communicative practice had a lot to do with that positive outcome.

Reference:

Arnett, R.C., Harden Fritz, J.M. and Bell, L.M (2009). Communication ethics literacy: dialogue and difference. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

As an organization, a faith community has multi-dimensional views of what constitutes the “good” that it aspires to reflect. Some constituents may define it as tending to the emotional and spiritual needs of the congregational flock, while others may interpret the good as integration with and serving the broader community. Fulfilling the teachings of the Torah, Bible or other sacred texts may constitute the good to others, and still others may interpret it as maintaining a well managed, fiscally sound organization that represents responsible stewardship of the community’s collective resources.

Myriad stories reflect these and other diverse perspectives to form the community of memory, connecting learnings from the past through the present to inform the unseen future of the organization. By virtue of its role in interpreting information and making decisions that have broad cultural implications, the leadership of the faith community, in the form of the board of trustees or equivalent, is at the nexus of this continuous transformation.

I once served on a task team that was charged by our board with updating and amending the congregational by-laws. One of the chief tasks was to reduce the number of trustees. Leading up to this assignment, a strategic planning process had determined that the board’s size was encumbering its ability to make decisions and conduct the Temple’s affairs effectively.

Our team recommended a systematic reduction in the number of at-large board members during subsequent nominating classes, and elimination of permanent reserved slots for the presidents of three affinity groups within the congregation. These groups represented three large and influential demographic segments, the Brotherhood for men, the Sisterhood for women, and SPICE (“Special Programs of Interest and Concern to Elders”) for seniors. Our reasoning was that most board members were members of at least one of the groups, and thus, the interests of the groups were already being served. The benefit to having their leaders on the board was superseded by the organizational imperative of reducing the size of the governing body.

The negative reaction from these groups and their agents was loud and emotional, and constituted a rhetorical interruption within the temple. Their leaders, citing the importance of the respective groups to the congregation, maintained that not only was the “routine” of their appointment appropriate, but our suggestion was an affront. The situation was exacerbated by perceptions

among Brotherhood leaders that the board did not adequately acknowledge their group’s volunteer and financial support for the congregation. Ultimately the board approved our recommendation to reduce at-large seats but rejected the other suggestion, largely as a result of a vigorous lobbying by the Brotherhood and SPICE. (The Sisterhood was ambivalent.)

In hindsight, I believe we adhered to several ethical communications behaviors to mitigate the rhetorical interruption – although we didn’t know it at the time (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 163)! The task team met with the leaders of each group to explain our reasoning, and held “town hall” style meetings with the congregation. Although neither activity was particularly pleasant for us, both represented attempts to listen without demand and be attentive to the situational dynamics and the ground of the Other(s).

But had we followed the dictates of dialogic ethics more closely, there may have been a different outcome. For example, we might have leaned less toward “telling” about our reasoning and more to learning from the Other in the moment, thus serving the need for reflective understanding of communicative action in the given situation. The history of these groups’ representation on the board was an important contextual element, to which we clearly did not give adequate regard. We certainly were open to compromise from the outset, but making a proposal instead of engaging in dialogic negotiation probably “poisoned the well” in terms of building trust.

I guess we should have seen it coming. Pragmatism and sound reasoning alone are not enough to win the day; when it comes to organizational and intercultural communications, the soft skills of listening, attentiveness, and dialogic negotiation define ethical competence, and enhance the likelihood for success (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 152).

Reference:

Arnett, R.C., Harden Fritz, J.M. and Bell, L.M (2009). Communication ethics literacy: dialogue and difference. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Here is the very rough draft of my project paper for Week 5. All comments are welcome.

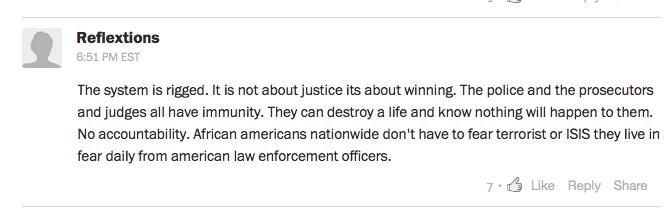

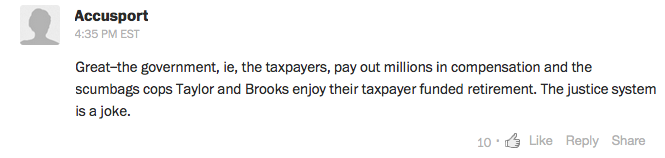

A recent story in The Washington Post about a civil verdict in favor of a man wrongfully convicted of murder provoked readers to explore the principle of justice in America, particularly as it relates to black citizens. Their discussion, if you could characterize the virtual interchange as that, illustrates the fallacy of unmediated online comment sections as legitimate exercises in public discourse ethics.

Post reporter Spencer Hsu described how a jury ruled that District of Columbia police violated the civil rights of Donald E. Gates, when it effectively framed him for the murder of a university student in 1981. Gates served 27 years in prison for a crime that he did not commit, before being exonerated in 2009 as a result of DNA testing (Hsu, S., 2015).

Not surprisingly, the story elicited strong opinions from readers, most of whom decried the injustice and called for punishment of the police officers involved in the case who deliberately falsified evidence in attempting to have Gates convicted. A typical comment: “Any detectives involved in this travesty should be stripped of any retirement benefits they may be receiving, lose every penny of wealth they may have accumulated, and lose any property they own. The only way to deter this type of judicial or law enforcement misconduct (and the term misconduct is way to mild for these actions), is to inflict serious and irreparable personal and financial pain. In this case, unfortunately, the only folks to feel pain will be the law abiding citizens of the District of Columbia.”

Some readers tied the case to the current national debate about perceived biases in the judicial system against black Americans, and the related “Black Lives Matter” movement. Others cited the case as an example of a fatally flawed system incapable of doling out justice consistently and fairly.

Given the flagrant nature of the case, hyperbolic sentiments are to be expected and some perhaps warranted. Many points were legitimate, while others were irrational (“Stripped of retirement?? They should be shot!”). A theme of what constitutes appropriate legal process provided examples of “undue confidence and unsubstantiated opinion,” when some readers weighed in only to be corrected by others apparently with legal training and experience.

Given the flagrant nature of the case, hyperbolic sentiments are to be expected and some perhaps warranted. Many points were legitimate, while others were irrational (“Stripped of retirement?? They should be shot!”). A theme of what constitutes appropriate legal process provided examples of “undue confidence and unsubstantiated opinion,” when some readers weighed in only to be corrected by others apparently with legal training and experience.

This particular collection of comments typifies why such online discussions are not suitable for protecting the public “sacred space.” Foremost, there was little or no balance in points of view evident. The discussion lacked legitimate voices of the judicial system, such as police officers, prosecutors, and judges. Although the story illustrated how the system failed, the public certainly would have benefited from an eloquent defense of the broader principles of justice involved, explanations for why the injustice occurred, and what can and is happening to prevent such problems from recurring in Washington and elsewhere. What about the voice of Gates or others who had been wrongfully convicted, or those of family members of the victims involved in their cases? Public accountability in the pursuit of public discourse ethics mandates “the communicative commitments of (a) diversity of ideas, (b) engagement of public decision making, and (c) a public account for continuing a communicative practice or changing that practice” (Arnett et al., 2009, pp. 102-103). All three would have been served by adding diverse perspectives to the discussion.

I have long believed that editors and content managers who oversee online news stories and their comment sections are committing journalistic malpractice but not taking a more active moderating role. In the spirit of First Amendment free expression and/or out of sheer laziness, they follow lais·sez-faire policies and only intervene for blatantly racist, sexist, or similarly offensive remarks. As a result, these comment sections rarely offer up any substantive conversations that might legitimately lead to societal benefit –- at least in proportion to the effort and number of words rendered in such spaces across the Internet. Most readers simply ignore these comments, much less learn anything from them.

Informed moderators charged with enforcing balance and well-reasoned comments would go a long way to correcting this problem. This may not be as difficult as it appears; the discipline involved is not so different from good old-fashioned editing of the caliber we used to see in newspaper and magazine reporting. Ensuring fairness, balance, well thought-out positions, and respectful exchanges would be a good start. There may be some risk that those with limited writing or communications skills could feel left out, but moderators could be trained to recognize and accommodate their needs in order to encourage participation. It would be worth the extra effort, given the potential benefit to the protection and preservation of our public realm.

References:

Arnett, R.C., Harden Fritz, J.M. and Bell, L.M (2009). Communication ethics literacy: dialogue and difference. California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Hsu, S. (2015, November 18). D.C.police framed man imprisoned 27 years for 1981 murder, U.S. jury finds. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com

Defining a personal narrative is not as easy as it first seems. That’s probably because we are not as accustomed to describing our narratives as we are living them. Opportunities are rare; the only ones that come to mind are a college essay, lecturing your children, the capstones of a resume or perhaps an online dating profile. The other challenge is distilling so much about a life perspective into one statement, which reminds me of the story about the Egyptian Pharaoh who directed an advisor to sum up all economic policy and wisdom into a single sentence. The advisor’s response was “There’s no such thing as a free lunch,” which itself could be someone’s personal narrative.

My life’s narrative would have to be the virtue in efficiency, or something similar. This approach sounds a bit mechanical and impractical, because life — as we all know — is complex and messy. Then again, cutting a direct path is often the best way to traverse a thicket. I tend to approach most situations and challenges by first asking rhetorically, “What is the best, most effective way of proceeding?” This construct was the “dwelling place” for pursuing and protecting my sense of the good (Arnett et al., 2009, p. 38).

\At its foundation, this is an editor’s mindset, and there is no coincidence that I have been a writer and editor since high school. In journalism school at UNC Chapel Hill, we were taught to be frugal with language. To shoe-horn an article into the news hole, pare unnecessary words like you would cut gristle from a steak. No more than 35 words in the lead of a news story. Why use two words when one will do? It was not unusual to get an assignment back with remarks to the effective of: “Nice work. Now cut the word count in half.” In addition to much tighter copy, that mandate delivers surprising clarity of thought and intent. Your readers always appreciate the effort. I suppose that is why Twitter is my social media channel of choice.

There are analogies in life. I tend to follow a short list of maxims, some of which have been borrowed from the editing process. Examples include being direct whenever possible, because people appreciate candor. Or avoiding clichés, because they are a clear sign that you really don’t have anything to say, don’t know what to say or how to say it. And honoring deadlines, because that reflects being reliable and trustworthy.

On a more spiritual level, “The Golden Rule” (see previous blog post) is a simple yet universal precept for navigating many situations, whether broaching an emotional subject with a friend or co-worker or allowing someone to merge into rush hour traffic. Other constructs imply similar brevity in thought, action and/or outcomes. Tell the truth from the start, because it’s a lot easier to remember the details than if you lie or exaggerate (a frequent lesson for my children when they were young). Listen before opening your mouth, because someone else may say what you are thinking, or better yet, have a better idea. Set an agenda and stick to it.

These and other guidelines are basically editing techniques for living. They help form a narrative that enables me to focus my time and energy on what is important. Like a well-written lead in a news story, perhaps my life will turn out to be just as compelling.

Reference:

Arnett, R.C., Harden Fritz, J.M. and Bell, L.M (2009). Communication ethics literacy: dialogue and difference. California: Sage Publications, Inc.

Upon review, it is apparent that “The Good” in my life is comprised of inalienable beliefs about, simply put, how people relate to one another, especially with empathy. The central belief is the so-called “Golden Rule,” or “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Also called the Ethic of Reciprocity, this concept is about as universal as there can be; in fact, versions exist in the writings of every major faith tradition. I believe this is due to the fact that the saying speaks to the fundamental behaviors and attitudes that contribute to a high functioning society regardless of historical context, such as mutual respect, empathy and compassion.

When people do not honor the “Golden Rule,” or place other beliefs over it, problems inevitably arise. Take for example the current news story about the school resource officer in the Columbia, S.C. high school who was fired for flipping the desk of a black student, dragging her across the floor and forcibly subduing her. The officer may not have behaved in this way had he first considered whether he

would have approved of similar treatment of his daughter. Similarly, the student may not have refused to comply with the teacher’s requests to stop using her cell phone in class (behavior which precipitated the officer’s action) if she had thought about how it would feel to be ignored or denigrated by someone else. This particular story was more complex, with racial implications, for example. But there is little doubt that it represents a failure by the people involved to show respect and empathy for each other at a basic level, the essence of the “Golden Rule.”

Another “good” in my personal and professional interactions is the importance of fairness and balance to understanding. Whether a news story or disagreement with a spouse or friend, the principle applies: you must try to see the situation through a different lens than your own. I have found this value especially helpful in leadership roles, such as on boards and committees. Never assume to know everything about a situation, and in fact, hearing different perspectives is most often beneficial in myriad and often unforeseen ways. Just the attempt to hear the opposing position can be profound in terms of maintaining trust in the group and making progress on the matter at hand.

There are other “goods” that are imperative, such as humane behavior toward animals. I’ve always believed that you can tell a great deal about a person’s morality by how he or she treats animals. The same holds true for cultures. But this is a more nuanced argument in a post modern world. I learned this in an undergraduate English class, when I wrote an essay about bullfighting. To me, the practice is inhumane and barbaric. However, a fellow student who was Spanish accused me of being an arrogant, ethnocentric American who believed in the supremacy of my culture and attempted to force values on others, out of context and with no regard for their rich histories and cultures. It was a rude awakening. I still believe bullfighting is inhumane, and I have the right to that opinion. But my view is not the only one that is valid. In hindsight, this was probably my first lesson in communications ethics literacy!